One of the great fictions clung

to by our legal establishment is the untouchable wisdom of the English jury.

Twelve men and women, good and true, convened to determine guilt beyond

reasonable doubt. Except of course when they don't. And occasionally,

spectacularly so.

From time to time there are assault cases reported where despite video, multiple corroborating witnesses and visible injury or similar evidence, unmoved by the forensic and testimonial parade a jury has returned a majority not guilty verdict. Court reports would mention "sympathy for his circumstances"; he’d lost his job, the victim had a prior caution etc. The facts apparently irrelevant in such cases being secondary to other factors .

We’ve seen it before. Climate

activists gluing themselves to roads acquitted despite clear breaches of the law because juries “understand their cause.” For many decades there have been instances where protesters trespassing at military bases have walked free. It’s not the legality being judged but the politics and in some cases perhaps the charisma of the defendant.

These aren’t just quirks; they’re known

quantities. Litigants in person can ask juries to ignore the law;

barristers can`t. Barristers sometimes count on jury “common sense” to

ignore the law when it doesn’t suit. It’s supposedly the unwritten safety valve of our

system. The formal word is “jury equity”; the informal reality is

selective application of justice.

To be clear, most jurors do their

best. But unlike magistrates who are trained, appraised, and generally held to

some level of consistency, juries operate as legal mayflies: brief, unaccountable and gone before the consequences have landed.

Perhaps it is time we

considered more transparency: not full public disclosures of deliberations; no

one wants mob-judged justice but at least a recognition that jury trials are

not infallible. A verdict isn't necessarily right simply because it came from

twelve people in a room with a foreman and a checklist, an appeal being rejected by the Court of Appeal and has been dismissed by the The Criminal Cases Review Commission.

The problem of course is that

criticising juries is something of a taboo. It's a bit like that totem, OUR NHS, our national treasure. If we are to have an honest

conversation about justice in 21st century Britain we must be prepared to

acknowledge that not all verdicts are wise, just or even comprehensible. To

pretend otherwise is to indulge in comforting fiction and fiction has never

been much of a foundation for justice.

It takes a certain type of

chutzpah to boast about acquittals before a trial has even begun. Yet that is

precisely what a member of Palestine Action recently did remarking, "The

public is on our side. Remember that being acquitted can happen and we’re seeing

it happen now." One might imagine such a

statement would raise eyebrows among those concerned with the rule of law.

After all, if verdicts are anticipated not on the basis of evidence or law but

on the perceived sympathy of a jury what does that say about the state of our

justice system? The message is clear enough: The law might say one thing but juries will say another because they like us. In other words conviction or acquittal is not necessarily tethered to legal merit but to public sentiment. That’s not justice; that’s a popularity contest. The courts are not supposed to be arenas for ideology. Yet in recent years certain activist groups, Palestine Action among them, have learned that the courtroom can double as a stage. They’re not just seeking to defend their actions but to put the system on trial. And juries in their secretive deliberations sometimes oblige. Today activist groups are increasingly calculating jury psychology as part of their tactical toolkit. Legal guilt is almost secondary.

There’s a disturbing logic to this: break the law, make the right noise and rely on a jury’s reluctance to punish those who claim moral high ground. The more emotive the issue; war, climate, colonialism the better the odds. It’s not just courtroom drama; it’s calculated legal theatre. Since some suggest that being a barrister is akin to treading the boards we should not be surprised that even some members of the legal profession agree that there are colleagues who are willing participants in this charade. And the consequences are far-reaching. When certain causes are seen to receive jury indulgence public faith in even-handed justice begins to erode: one rule for activists another for everyone else. Ask the man convicted of criminal damage for scratching a neighbour’s car if he had the luxury of moral justification that the hooded trespassing paint sprayer of military jets claims.

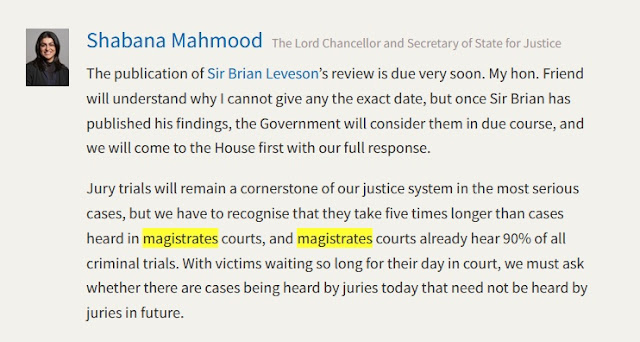

Juries are a cornerstone of our

criminal justice system. But they are not infallible nor immune to influence.

When defendants begin campaigning to jurors, not before the judge, the balance

has already shifted.

One might have hoped that those

charged with criminal offences would meet their day in court with humility, not

hubris. But humility is in short supply when you’ve discovered how to turn the

jury system into a political loophole. Consider that open boast above from a

Palestine Action member, made with the confidence of someone not fearing

justice but anticipating a sympathetic audience. Will we have to follow the Americans in extending the right to exclude would be jurors?

Translation? Break the law,

wrap yourself in a fashionable cause, and let the jury do the rest. Legal guilt

is negotiable when ideology is your shield.

This isn’t brave resistance; it’s cynical manipulation. It’s trial by politics not trial by evidence. What these defendants are really banking on is not the strength of their case but the predictable failure of jurors to apply the law when feelings get in the way. And they’re not wrong. Recent acquittals of activist vandals some caught red-handed have shown that for certain juries a cause deemed righteous excuses criminal damage. Smash up a weapons factory or spray paint government buildings and if you cry “human rights” loud enough, you might just walk free. The more performative the better. Hence the accusation at the investigative stage against police and CPS of two tier justice.

For those of us who sat for

decades on the bench striving for consistency, fairness and fidelity to the law

this is not just frustrating. It is corrosive. It mocks the entire foundation

of the criminal justice system: that the law applies equally, regardless of

politics, passions, or protest signs. Worse still, this selective

indulgence sends a message to the public: some offenders are more forgivable

than others not because of what they did but because of why they say they did

it. That’s not rule of law; it’s rule by narrative.

Let’s be clear: jury trial is a

cornerstone of English justice. But when it’s treated as a get-out-of-jail-free

card for the ideologically aligned it risks becoming a constitutional

liability. If the law bends only for those who shout the loudest we don’t have

justice: we have judicial theatre with a pre-approved script.

Perhaps a modernised version of the system witch finders employed for centuries in determining a woman`s guilt or innocence to a charge of practising witchcraft is a sub conscious underlying feature of facts being abandoned: the woman was tied to a stool which was immersed by a wooden beam in a lake or river. After one or several immersions if she survived she was considered guilty and punished and if she drowned her innocence had been established.

It`s increasingly obvious that it`s only after they retire that the most senior judges voice their often critical comments on the legal system. Of course their conversations with government whilst they are active are top secret. I suppose that process succeeds depending on which side of the judicial fence one is standing to view it.

And those of us who actually

believe in equal justice? We're expected to sit quietly and clap from the

gallery.

No thanks.